Mumbai’s Massive Gargai Dam Push: The High-Stakes Project Aiming to Secure the City’s Next 100 Years of Water

For a city that adds nearly 200,000 residents every year and consumes close to 3,900 MLD of water daily, long-term water security is not merely a planning challenge but a survival imperative. Mumbai’s search for sustainable, resilient water sources has spanned decades, often constrained by geography, ecology and administrative complexity. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s latest move, floating a tender to construct the Gargai river dam in Palghar, signals the beginning of the city’s most ambitious water augmentation project since the Middle Vaitarna Dam in 2014.

The proposed Gargai reservoir is designed to become Mumbai’s eighth water source, adding 450 MLD to the supply network. With the tender pegged at Rs. 3,040 crore, the project represents both a technological milestone and a governance stress test. It has been under discussion for nearly a decade, delayed repeatedly by environmental, interdepartmental and rehabilitation-related considerations. Now, with administrative clearances underway and the tender floated, Mumbai appears ready to advance a project that will define its water future for the next century.

A Mega-Structure Designed for Long-Term Security

At the heart of the plan is a 69-metre-tall dam and a 1.6-kilometre water supply tunnel designed to move water through a 2.2-metre-diameter conduit. The engineering approach is built around integration rather than isolation. Water from the Gargai reservoir will be channelled through a tunnel cut across the hillock separating the two basins into the Modak Sagar reservoir, one of the city’s existing water hubs, before being distributed across Mumbai. This basin-to-basin connectivity allows Mumbai to leverage existing infrastructure while expanding supply.

The civic body has also proposed building a guest house, an auditorium and an administrative complex around the reservoir periphery, reflecting a model where water infrastructure evolves into multi-utility spaces supporting monitoring, research and public administration. This approach aligns with global trends where hydrological assets are increasingly integrated with tourism, conservation and institutional functions.

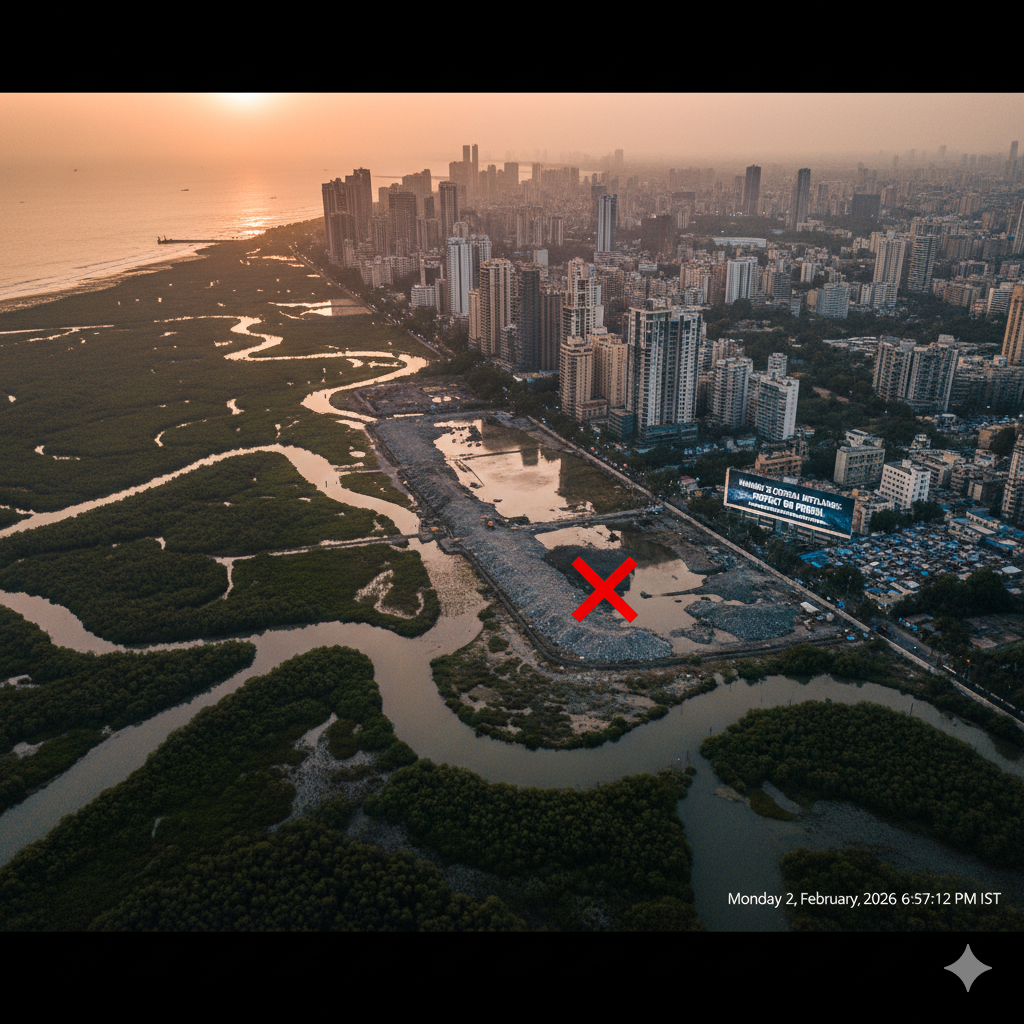

The Forest Equation: Land, Loss and Ecological Calculus

The project site sits inside the Tansa Wildlife Sanctuary, occupying 658 hectares of forest land. The ecological implications are significant, with approximately 3.1 lakh trees expected to be felled. While the BMC has secured clearances from the National Wildlife Board, the Forest Advisory Committee and the Forest Development Corporation of Maharashtra, the scale of tree felling mandates additional approval from the Union Environment Ministry.

Compensatory afforestation plans are already underway, with land in Chandrapur district demarcated last year. Yet, the broader question is how cities negotiate the tension between conservation and demand. As climate patterns become increasingly erratic and rainfall distribution grows unpredictable, the ecological calculus becomes more complex. Large dams bring guaranteed supply but also require governments to adopt stronger environmental safeguards, transparent monitoring and long-term ecological rehabilitation frameworks.

Mumbai’s challenge mirrors that of many global megacities: the need to balance environmental conservatism with infrastructural necessity. The Gargai project will test whether these competing priorities can be harmonised through modern planning and sustained administrative oversight.

Rehabilitation: The Human Center of Infrastructure

Beyond environmental considerations lie the social implications. Two villages, Ogda and Khodada, will be fully submerged, while four others, Pachghar, Tilmal, Phanasgaon and Amle, will be partially affected. Project-affected families will be relocated to 400 hectares of Forest Development Corporation land in Devli taluka, Palghar.

Rehabilitation in large water projects has historically been the Achilles heel of public infrastructure in India. Timely compensation, transparent land records, livelihood transitions and social integration form the core of successful relocation. With nearly six villages impacted, the Gargai dam becomes not merely an engineering project but a human development exercise. The success of the initiative will depend significantly on how rehabilitation is sequenced, communicated and executed.

For a city dependent on external water sources, nearly 95% of Mumbai’s water comes from reservoirs located outside its boundaries, maintaining the trust of host communities is critical. The Palghar region’s cooperation will be central to the project’s operational stability over the next decade.

Timelines, Costs and the Infrastructure Governance Test

Once initiated, the construction is expected to take six years. Large-scale hydrological projects typically undergo time overruns due to weather constraints, land acquisition delays and inter-agency coordination challenges. The Rs. 3,040 crore cost estimates will similarly face inflationary pressures and periodic revisions.

However, the Gargai project could benefit from Mumbai’s improving project management ecosystem. The city’s recent successes in coastal road tunnelling, sewage treatment plant upgrades and transport engineering have strengthened the administrative muscle needed to deliver complex projects. Yet, the critical question is not execution alone but governance continuity. Mega-projects often span multiple political cycles, making institutional memory and documentation essential.

The tendering process marks the beginning of a multi-year governance commitment where engineering, environment, finance and rehabilitation teams must operate with synchronised precision.

Mumbai’s Water Future and the Strategic Case for Gargai

The city’s daily water demand is expected to rise significantly by 2035 as population density increases and industrial clusters expand. Without new supply augmentation, Mumbai risks facing structural shortages, particularly during extended monsoon deficits. The Gargai reservoir, by contributing an additional 450 MLD, provides a buffer that stabilises supply planning while reducing vulnerability to rainfall variability.

More importantly, this project represents a shift from reactive water management, dependent on emergency restrictions, to long-term, capacity-building strategy. Hydrological diversification is becoming a necessity for large metropolitan economies, and Mumbai’s move towards its eighth water source underscores the seriousness of its planning horizon.

The Gargai dam is therefore not simply a construction project; it is a strategic investment in resilience. If executed with environmental sensitivity, administrative coherence and engineering discipline, it could become one of Mumbai’s defining infrastructure assets for the next century.