Mumbai Launches Bold Push to Reclaim 500 Acres of Encroached Land for Public Use

Mumbai, a city where every acre is contested, every open space is precious, and every unauthorised settlement reshapes the urban landscape, is preparing for one of its most ambitious land-reclamation drives in recent years. Mumbai Suburban Guardian Minister Mangal Prabhat Lodha has announced that the government will take back nearly 500 acres of encroached land across the suburban district and convert it into public-use spaces. The move marks a significant escalation in the city’s fight against illegal construction, environmental degradation and the civic vulnerabilities that emerge when public land slips out of public control.

The announcement came after Lodha chaired a high-level review meeting at the Bandra Suburban Collector’s Office with District Collector Saurabh Katiyar and senior officials to assess ongoing anti-encroachment operations. The discussions made clear that Mumbai’s encroachment challenge is not a sporadic urban governance issue but a complex, deep-rooted structural problem.

A City Under Pressure: Encroachments Rising on Government and Mangrove Land

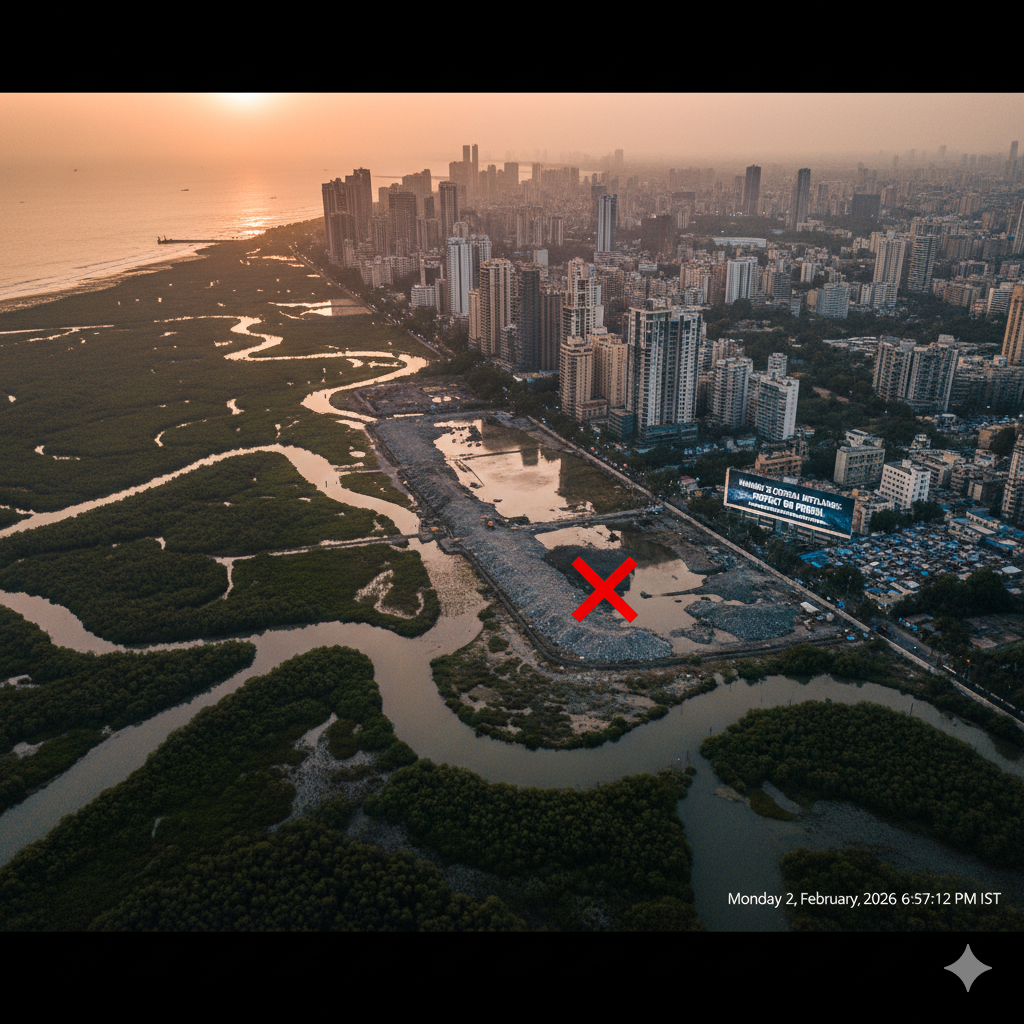

Briefing the media after the meeting, Lodha said that illegal construction has intensified across government-owned plots and mangrove belts in several suburban pockets. The pattern is neither new nor unique to Mumbai. However, the scale is becoming increasingly unsustainable. With limited land availability and an exploding population, every acre lost to unauthorised development pushes the city further away from creating green corridors, public parks, schools, health centres and civic infrastructure.

Mangrove encroachments remain particularly concerning. These ecosystems are Mumbai’s natural flood buffers, and any construction on them increases climate vulnerability, particularly in low-lying suburban areas.

Malad–Malvani: The Most Alarming Case Study

Among all the identified pockets, Lodha described the situation in Malad–Malvani as “especially alarming.” In the first phase of action, the administration has already cleared 9,000 sq. metres of encroached land. But this, Lodha warned, is only the beginning. Clearing structures is not a permanent solution unless the land is secured against reoccupation, a recurring challenge in previous anti-encroachment drives.

The minister emphasised that protecting open land is now not just a governance responsibility but a civic necessity. “Large-scale encroachment is obstructing the administration from providing essential services to citizens. The government will take firm possession of these lands and use them for public welfare,” he said.

Expanding Enforcement to High-Risk Zones

Lodha directed officials to intensify operations in other vulnerable zones, including Mankhurd, Kurla and Govandi, all areas where open land is routinely captured through organised encroachment networks. Such pockets often evolve into dense informal settlements with weak building safety standards, high fire risk, limited sanitation access and inadequate public services.

What begins as a few temporary structures often becomes a permanent settlement in a matter of months, a trend that strains local infrastructure and complicates urban planning for decades.

Startling Discoveries: Anganwadi Centres Occupied for Commercial Use

During inspections in Malad–Malvani, officials uncovered an alarming misuse of public infrastructure: 28 Anganwadi centres, essential for child nutrition, maternal health and early education, were found illegally occupied and repurposed as meat stalls, paan shops and commercial units.

This misuse goes beyond encroachment; it represents a direct diversion of public resources meant for vulnerable communities. Lodha instructed that criminal cases be filed against those responsible, underscoring a zero-tolerance approach toward the commercial exploitation of social infrastructure.

Security Concerns and Alleged Illegal Settlements

In one of the strongest statements of the review meeting, Lodha raised concerns about what he described as large-scale settlement of Bangladeshi and Rohingya immigrants in Malvani, alleging that the activity was facilitated by a local MLA. He claimed that several individuals had obtained forged identity documents and illegally registered themselves as voters.

Lodha pointed out that the number of registered voters in Malvani has doubled over the past decade, a demographic spike that officials believe warrants deeper scrutiny. He warned that such unchecked settlements pose potential security risks to Mumbai, particularly in areas where illegal construction is intertwined with identity fraud and organised land capture.

While these allegations will require formal investigation, they highlight a critical governance challenge: when encroachment overlaps with identity manipulation, the implications go beyond urban planning and enter the domain of security and law enforcement.

Public-Space Development and Long-Term Planning Begin

District Collector Saurabh Katiyar informed the minister that preliminary planning has begun to classify reclaimed open spaces and initiate public development work. This includes identifying land for parks, community facilities, public buildings and other amenities that Mumbai urgently needs as its population density continues to rise.

Deputy Commissioner of Police Sandeep Jadhav also confirmed that criminal cases will be registered against individuals found illegally occupying government land. The coordinated involvement of revenue authorities, policing units and local administration suggests a shift toward more structured and sustained enforcement.

A Structural Move Toward Rebalancing Mumbai’s Urban Equation

The decision to reclaim 500 acres is more than a land recovery exercise. It is an attempt to rebalance Mumbai’s urban equation, one where development pressures, population growth and political complexities often overshadow long-term public interest.

Cities thrive when land is used equitably, transparently and sustainably. Encroachments erode this balance, creating fragile environments where infrastructure falls behind and services fail to keep pace with need. Reclaiming land for public use is therefore both a governance imperative and a social investment.

If the enforcement continues with the consistency outlined by the administration, Mumbai could regain precious public space and build a more resilient urban future. But the test lies not just in clearing illegal structures, it lies in preventing their return, ensuring lawful development and restoring land to the citizens it rightfully belongs to.

.png)